The History and Continuing Practice of Batik

The traditional labor-intensive medium of batik—creating images and patterns with dyes on textiles using a wax resist technique—goes back thousands of years and is thought to have originated in Indonesia. Some researchers have suggested that batik may have roots in 6th and 7th century India, but Indonesia has become so strongly identified with this creative process that on October 2, 2009, UNESCO officially recognized Indonesian batik, both the freeform written batik (batik tulis) style and traditional stamped batik (batik cap)—as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Since then, Indonesia celebrates National Batik Day annually on October 2nd when all Indonesians, adults, and children alike, are encouraged to wear batik.

Stylistic Craft

While the island of Java is recognized as the home of the best traditional batiks in the world, the craft of batik has been assimilated throughout Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, and in Europe during the 19th century, the result of trade driven by colonialism. The two primary stylistic forms of batik are geometric motifs, which include some of the earliest examples, and free form designs, which are most prevalent in contemporary work. These two approaches can be divided into one of four types of batik; Batik Blok (Block Printing Batik), Batik Skrin (Screen Printing Batik), Lukis (Hand Drawn Batik) and Tie Dye Batik. While specific patterns and colors are associated with certain geographical locations, they also vary widely based on the creativity of the maker.

The word “batik” is possibly derived from the word “ambatik,” which means “a cloth with little dots.” The suffix “tik” means “little dot,” “drop,” “point,” or “to make dots.” The term may also originate from the Javanese word “tritik,” a resist process for dying where the patterns are embedded in textiles by tying and sewing areas prior to dying, similar to tie dye techniques. Basic materials include a textile, wax-resistant dyes, and melted wax. In some cases, another medium of resist like rice paste is used. The selection and preparation of the cloth is essential in insuring work of the highest quality. It must have a high thread count and be washed or boiled in water to make it a receptive surface for the colored dyes. The patterns and designs can be intricate, but the basic tools are simple. A canting is the spouted container that holds and applies the melted wax like an ink pen. It is the drawing tool used in freehand design and is also the most time-consuming method of application when creating a fabric with a repeated geometric design. To meet the growing demand for batik in the 19th century industrialized economy, a copper stamping tool or block was developed, enabling a higher volume of production.

Before dying, the design is transferred, or traced onto the cloth. Then the wax is applied in subsequent layers, with the lightest areas covered first, followed by layering wax as the dye baths proceed with ever deepening color. Original colors, typically beige, sepia, brown or black were made from natural ingredients. The oldest color was blue, which was made from the Indigo plant. Today a huge range of colored dyes, both natural and synthetic, are available.

Team Dyes

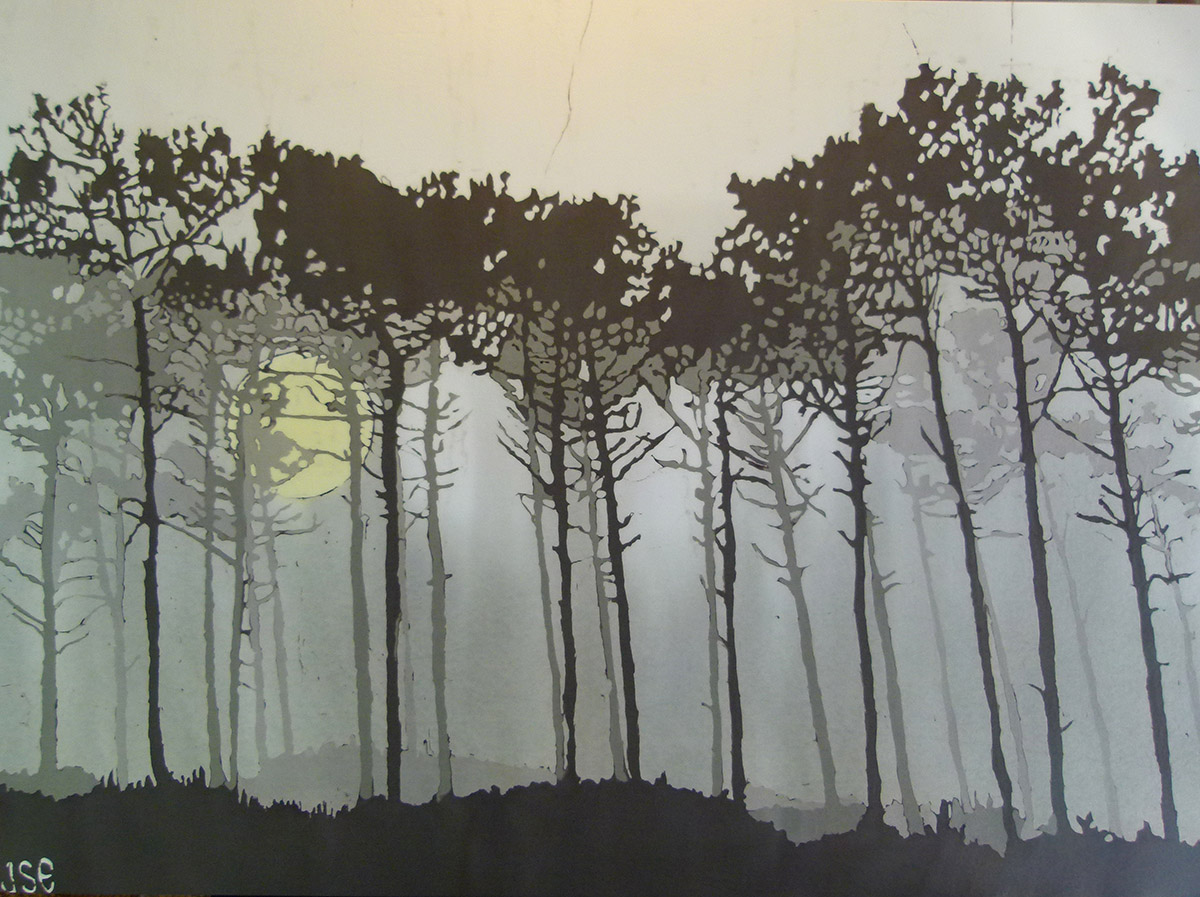

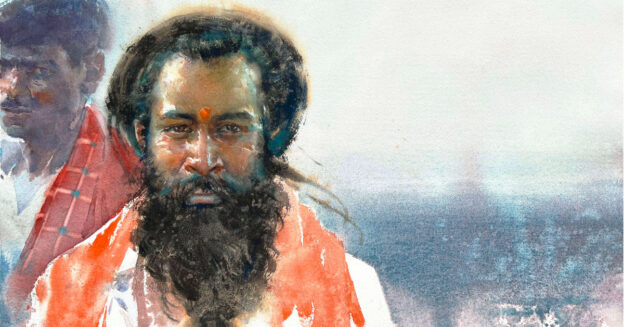

Besides adorning yourself with batik clothing, you can also appreciate a framed work of batik art made by contemporary artists like the husband/wife team of Beth and Jonathan Evans. Batik is their primary creative medium and is central to their professional, personal, and social lives—and their work is stunning. Beth practices a pointillist, atmospheric style while Jonathan favors portraiture and a more figurative approach. Jonathan states, “As Chairman of the International Batik Guild I am proposing 2024-25 be designated the Year of Batik. I am pushing hard to legitimize batik as a valid — and terribly difficult — art medium and to change its unfortunate image of being akin to tie-die and women’s ‘soft’ craft. We are planning exhibitions all over the world, a lot of teaching, articles, and more.” The couple runs Shalawalla Gallery in Colorado, where they teach batik and sell their work along with other batik items culled from their world travels. This dynamic duo recently received a UN Economic Development grant to teach batik and set up a business in St. Lucia in the Caribbean. They will be working exclusively with organic dyes that can be grown on the island. Batik is a perfect example of an ancient art form that remains powerful and relevant today.

For more about batik, feel free to check out this piece about Ryan Fox, whose work Amsterdam Skyline won second place in out 15th Annual Watermedia Showcase.

Not my type of art work.