Unmasked: A New Exhibition by Suzanne Benton

A new exhibition featuring the welded-metal masks of artist Suzanne Benton celebrates the indomitable female spirit.

By Cynthia Close

Pioneering feminist artist Suzanne Benton’s career spans nearly seven decades and extends to 32 countries. “Suzanne Benton: Unmasked,” a new exhibition at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury, Conn., recognizes her legacy of feminist activism by presenting female figures from myth and history in her signature welded-metal masks and color-rich monoprints. Telling the stories of influential women across time and space, this exhibition, from March 17–May 5, 2024, highlights the contributions of women to global history.

Artists Magazine featured Benton in a 2022 issue; below is an excerpt of the article by contributing writer Cynthia Close.

More Than a Pretty Face

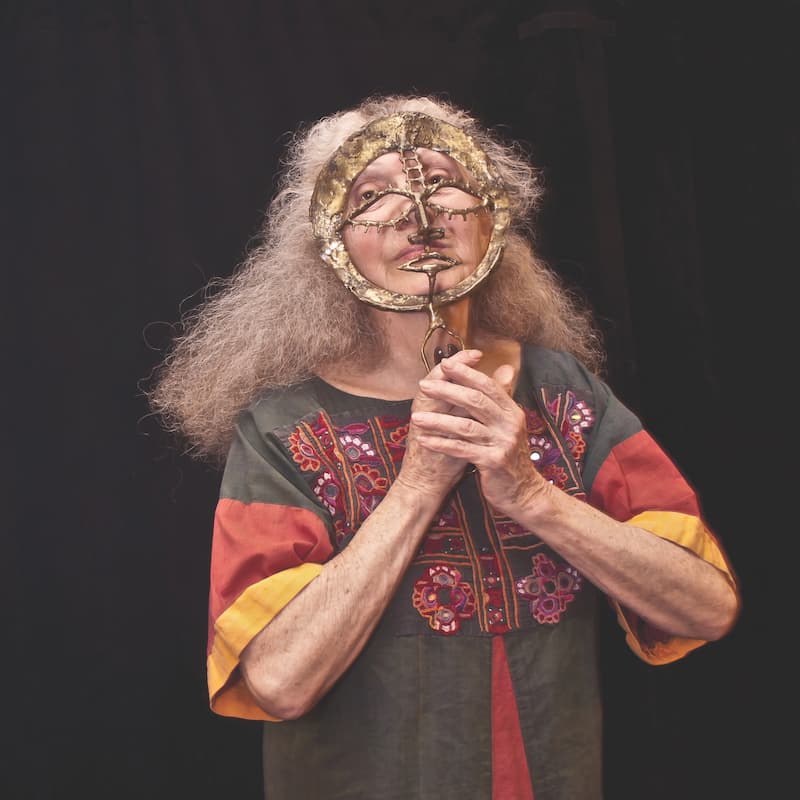

An abundant froth of silvery hair springs out from behind the enigmatic, yet commanding, mask that shields the face of multimedia artist Suzanne Benton. That hair is the only clue indicating the age of this effervescent storyteller. Born in Brooklyn in 1936, now near the end of her ninth decade, Benton is directing part of her considerable creative energy to the art of masked performance.

Rather than treating masks as accouterments concealing a wearer’s identity, the artist sees them as evocative objects that reveal the underlying myths surrounding female characters. “I wanted to look back to the strong women who were the roots of Western civilization,” she says, “particularly those in religious texts, such as Lilith, Esther, and Sarah.”

The artist’s masks are unyielding—more sculpture than costume—and are welded from bronze, copper, aluminum, steel, and various metal fragments that she may have scavenged from a junkyard scrap heap.

In 1975, Benton wrote The Art of Welded Sculpture. This comprehensive treatise covers every detail of the art-making process—equipment needed, studio requirements, methods and materials, and presentation—as well as her philosophical perspective of an artist’s responsibilities to herself and her audience. This groundbreaking book targeted a female audience during a time in which artists who created welded-metal sculpture were almost universally male, and their work was abstract—and devoid of the figurative storytelling aspect that Benton espoused.

The Forging of the Artist

At the formative age of three, when most toddlers explore the world under the ever-watchful eye of a parent or other caregiver, Benton’s mother taught her daughter how to cross the busy street in front of their Brooklyn, N.Y. apartment by herself so she could play in Prospect Park. This approach would be seen by most parents today as risky at best, but it fostered the artist’s fearless independence, a trait that has served her well in her nomadic, creative life.

Benton also recollects that a dearth of toys forced her to find other ways to amuse herself and promoted observation skills—which, she points out, are important in the development of any artist. “Alone in my infant bedroom, I became skilled at observing the world, particularly the effects of light as it poured through my window,” she says. “Light became my entertainment.”

Benton’s father also may have had an unwitting influence on the artist’s work. During WWII, due to shifting economic dynamics, he left his job in advertising and became a riveter—foreshadowing the role that metalworking would eventually play in Benton’s mask-making.

Majoring in art at Queens College provided the necessary guidance for Benton to become the prolific sculptor, printmaker, painter, and performance artist she is today. “The first artist to attract my attention was Cézanne, but it wasn’t until I had chosen welded sculpture that I recognized my love for form and attraction to metal as my medium,” says Benton. “I came to know power with the welding torch.”

Performing With Masks

In her mask-making workshops and performances, Benton has employed irony and humor to actively engage international audiences in and beyond the U.S., including Europe, East and South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The driving force in her life and work, however, is the long history of injustice inflicted on women. The artist became a single mother of two children while forming Connecticut chapters of the National Organization for Women (NOW), founded in 1966 by ardent feminist Betty Friedan.

The 1970s gave way to a great wave of feminist artistic expression. In 1971, the Museum of Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, New York City, mounted an exhibition of Benton’s steel and bronze masks. At the opening, Benton, along with a young theater arts student, Judith Hannah Weiss, performed a masked retelling of the story of Sarah and Hagar, based on the Old Testament account from Genesis. This was the first outdoor performance ever held at Lincoln Center.

Sarah and Hagar

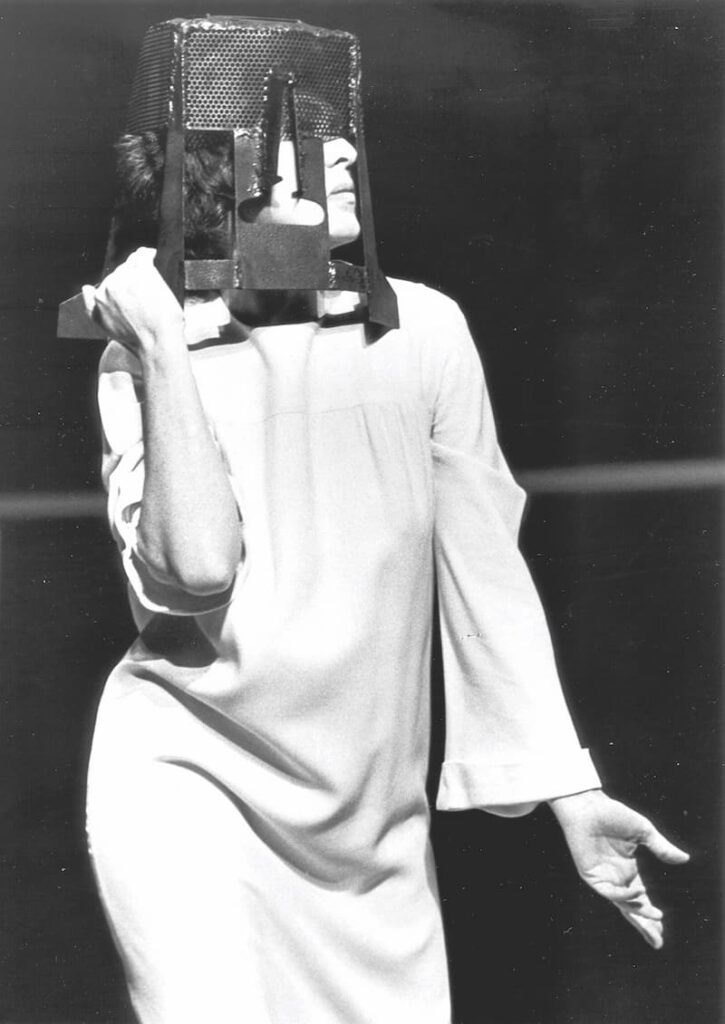

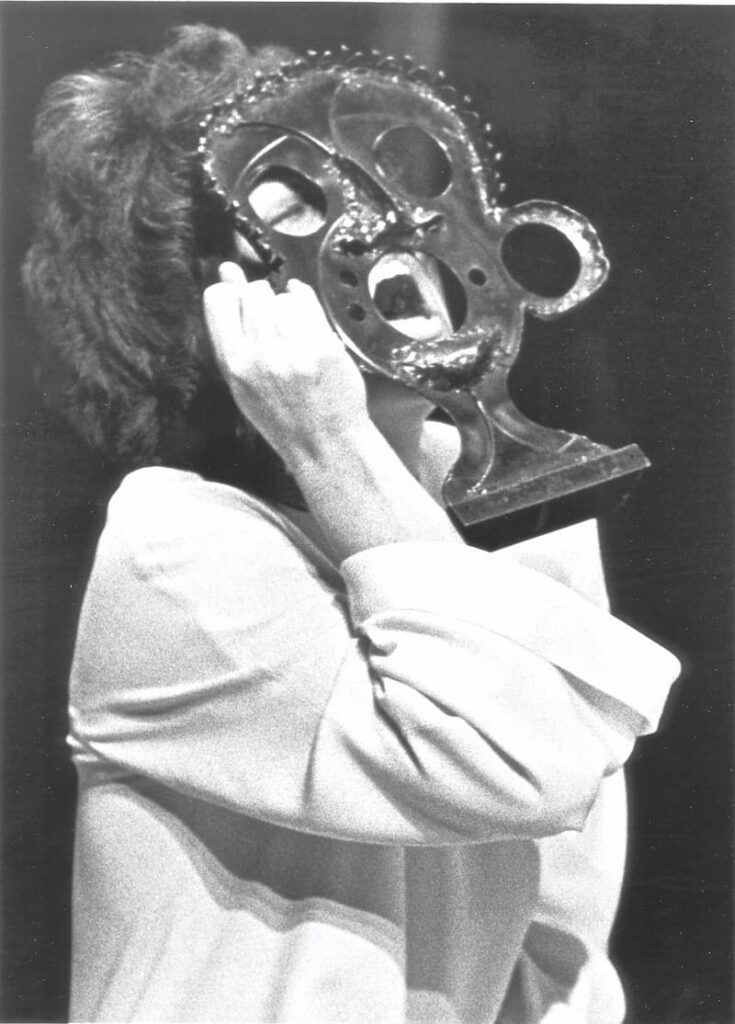

In the biblical account, Sarah, having determined that she was barren, arranged to provide an heir for her husband, Abraham, through Hagar, Sarah’s handmaid. Hagar conceived and bore a son, creating tension between the two women. The situation worsened when Sarah miraculously gave birth to her own son through Abraham. These two photos show Benton’s 1972 performance of the story, costumed with the artist’s masks.

Left: Suzanne Benton wearing mask of Sarah (steel, 12x14x13) Photo: Lele Stevens; Right: Suzanne Benton wearing mask of Hagar (steel and copper, 12x14x13) Photo: Claudia Stevens

From 1973 to 1975, Benton served as the chairperson of the NOW Women in the Arts National Task Force and was the founder and organizer of Metamorphosis, the first women’s art festival of second-wave feminism.

Since the 1970s, she has given workshops, performed in more than 31 countries, and exhibited her work in more than 150 solo shows worldwide. During one of her sojourns in Köln, Germany, in 1982–83, she created 27 masks, including Hagen, on the theme of the Holocaust—an undertaking prompted by her recollections of the nightmarish stories told by German immigrants who’d fled the Nazis and lived in her family’s New York City apartment building.

The Technique

Benton balances the practical reality of welding with a philosophical outlook. “Fire can be a frightening thing,” she says. “Mastering the fear will give you strength in all areas of your life.” Her technique is intuitive. “In my sculptural process,” she says, “the tasks of adding, covering, and making seemingly illogical joinings are blended into what can be described as ‘stream of consciousness.’” The layering of metals is akin to the collage technique she employs in her printmaking.

Color doesn’t play a major role in Benton’s masks. In fact, she says, “I mourned color when I started creating sculptures.” In more recent years, however, she has allowed her love of color to bloom in Chine collé monoprints and searingly vibrant oil paintings.

The Future

Masks are inscrutable objects of magic and imagination that have played symbolically powerful roles in many cultures throughout history. Benton continues to be a modern trailblazer in the field, laying the groundwork for contemporary artists to explore the meaning of their lives through the art of mask-making. She’s currently writing a memoir, The Spirit of Hope.

About the Author

Cynthia Close earned an MFA from Boston University and worked in various art-related roles before becoming a writer and editor.

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!